Andy's West Highland Way Hike

Posted by Andy Neil on Sep 09, 2025

Retracing My Footsteps on the West Highland Way

I first walked the West Highland Way (WHW) eight years ago, when I was relatively new to long-distance walking. The WHW was a seminal experience for me. I had completed the Cleveland way, but the WHW, at that time, felt so much more remote, like a real adventure north of the wall in an unforgettable landscape. It inspired me to keep hiking and to seek out other long-distance paths. Since then, I’ve walked thousands of miles across England and Scotland. What once felt daunting has become second nature. The WHW was the foundation for that transformation. So, when Brian, my American friend with whom I have walked hundreds of trail miles, got in touch to tell me he was planning on hiking the WHW, I jumped at the chance to retrace my steps.

Back then I remember setting off with a pack that was far too heavy and a nervousness about whether I was really cut out for long-distance walking. Every stage felt like an unknown country. Returning now, with lighter gear and steadier legs, I wondered how the trail itself would feel. Smaller, easier, somehow tamed? Or would it remind me again that the Highlands never quite let you off easy.

Brian took the high road (a plane), and I took the low road (a train), and he, indeed, was in Scotland before me. We met at Glasgow Queen Street station and, after a quick catch-up, made our way to the start of the trail, Milngavie. There are several ways to get to Milngavie from Glasgow, but we found that the simplest, quickest, and cheapest option was an Uber, which took less than 20 minutes. We quickly grabbed a few supplies and were ready to go.

Day One, Milngavie to Drymen 12.8 miles (20.70km)

The official start of the WHW is marked by an obelisk in Milngavie’s town centre. Once we had asked a friendly local (I imagine this is a daily occurrence for the residents of Milngavie) to take a photo of us, we were off. The path meanders through parkland, slowly, imperceptibly transitioning to woodland as we left the suburbs of Glasgow behind. The walking was straightforward, and the miles passed as we chatted. The John Muir way intersects the WHW near Carbeth Loch, and it is here that the views open-up for the first time, a sneak peek of what we could expect from here on. The Strathblane Hills, sentinels of the Campsie Fells, made for an impressive sight as we walked northward past the Glengoyne Distillery.

About half a mile beyond the distillery, almost precisely the day’s halfway point, we reached The Beech Tree Inn. It serves all manner of refreshments and WHW souvenirs; t-shirts, tea towels, socks; if you can print a Highland cow on it, they sell it. From here on, every shop along the Way seems to stock WHW merch. This is a very popular first-day lunch stop for weary walkers, offering hearty comfort food and even a small petting zoo. We opted for a haggis and sweet chilli sauce toasty, the epitome of fusion food. While having lunch, we met Mark, the first of our hiking “bubble”, that we would be constantly “leapfrogging” throughout the day, and more often than not, drinking with on an evening.

Shouldering our packs, the route continues through rolling farmland towards the hamlet of Gartness, with its old stone cottages and impressive bridge. It began to rain steadily as we undertook the brief stint of road walking toward our end point, Drymen.

The rain continued as we made our way along the Stirling Road toward the Winnock Hotel, our accommodation for the night. Here, we quickly dried off and changed, then made our way over to the Clachan Inn, which claims to be Scotland’s oldest licensed pub (est. 1734), where we sampled a few local beers, some Glengoyne whisky (the distillery we had passed), and a venison burger.

Brian had been on the go since leaving Washington, D.C., several thousand miles away. I’d been travelling since my 5.30am train from Middlesbrough to Carlisle, so by the time we finished our second (or third) dram, we were both well and truly knackered and were in bed and asleep by 9.

After just one day, the WHW was already working its magic again, rain, whisky, and haggis, a splendid first day on the trail.

Day Two, Drymen to Rowardennan 15.4 miles (24.9 km)

Despite us having an early night, we took advantage of a late start and a sleep-in. We then went in search of sustenance, grabbed a coffee and a Lorne sausage bun and set off. The path out of Drymen heads north to the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park. Here, we saw many walkers packing up their tents after a night of wild camping. In the woods, the path splits in two: south for the easier stretch towards Balamaha, but our northern path leads you up onto the moors under the gaze of the iconic Conic Hill.

Conic Hill is the first real climb of the WHW (if you choose to do it), but the views over and across Loch Lomond make it one of the highlights of the whole trip. My advice: if you have good weather, go for it. It's a short, sharp slog up onto the shoulder of the hill. Here we stopped and enjoyed some refreshments and took in the views over the largest body of water (by area) in the UK.

On my first WHW, I remember staring out at Loch Lomond and thinking it was endless, the far shore impossibly distant. This time, I knew what was coming: the boulder scrambles, the hidden coves, the long pull to Inversnaid. But instead of dread, I felt anticipation. Familiarity hadn’t dulled the beauty; it sharpened it.

It wasn't until we started descending that we realised what an incredibly popular climb Conic Hill is. Some quarter of a million people climb it each year, and as we descended, the crowds thickened. We eventually made it down to the car park and visitor centre. We were about halfway through our day's hiking and once again the WHW provided a perfect stop for lunch. We grabbed a pie and a coffee at St Mocha in Balmaha and basked in the midday sun.

Balamaha is a picturesque village on Loch Lomond’s shore. It is considered the gateway to the Scottish Highlands, as it sits on the Highland Boundary Fault - a geological feature that separates the Lowlands from the Highlands. From Balmaha to Rowardennan, the Way hugs the eastern shore of Loch Lomond, undulating through native oakwoods and pebbled coves. We were both excited about the walk along the bonny banks and the walking did not disappoint.

There were a few small climbs that, in the heat of the day, sapped my energy, but overall, the walking was pleasant and we made perfect time. We soon made it to Rowardennan, a small hamlet nestled at the foot of Ben Lomond (974 m), Scotland’s southernmost Munro. We toasted the end of the day in the Clansman bar where we once again met up with Mark who was heading off to find a suitable campsite. We made for the Rowardennan lodge youth hostel, our bed for the evening.

The first day had been a pleasant stroll through gentle countryside, but today the Way had shown us what it truly had in store for the rest of the journey.

Day Three, Rowardennan to Inverarnan 13.7 miles (22.2 km)

Despite sleeping in a room with eight strangers, I slept well, showered, and was up for our continental breakfast early. We grabbed our packed lunches, a gleeful experience reminiscent of school trips and we were on our way.

The northern stretch of this remote section along the loch shore has a well-deserved reputation as being one of the most challenging yet one of the most scenic stretches of the way. The narrow, rocky footpath undulates through ancient oak forests, scrambling over roots and rocks. Only later did we learn that three hikers had been rescued by boat here the day before after serious falls.

It was a hot day, we took the opportunity to doff our packs, roll up our trouser legs and wade into the calm, crystal-clear waters of the loch to cool off. We dipped into our packed lunches and took in the tranquillity of the loch.

Once again, by midday, the trail provided a suitable spot to rest for lunch. Here, the cascading Inversnaid Falls flow dramatically into the loch below. The Inversnaid Hotel, a Victorian-era hotel right next to the falls, is a welcome oasis, we took the opportunity to refuel. The day’s walking had been strenuous so far, but it would only become more challenging after this small respite. Pushing on, the final section by the loch is a rollercoaster of up-and-downs, scrambling over boulders one moment, hopscotching between roots the next.

Eventually, mercifully, we reached the end of the loch, and after a brief climb onto a high knoll, we gazed back bidding farewell to the shimmering expanse of Loch Lomond. From here, the path, now wide enough to walk two abreast, gently descended into wide, expansive glens that we would follow until our end point, Fort William.

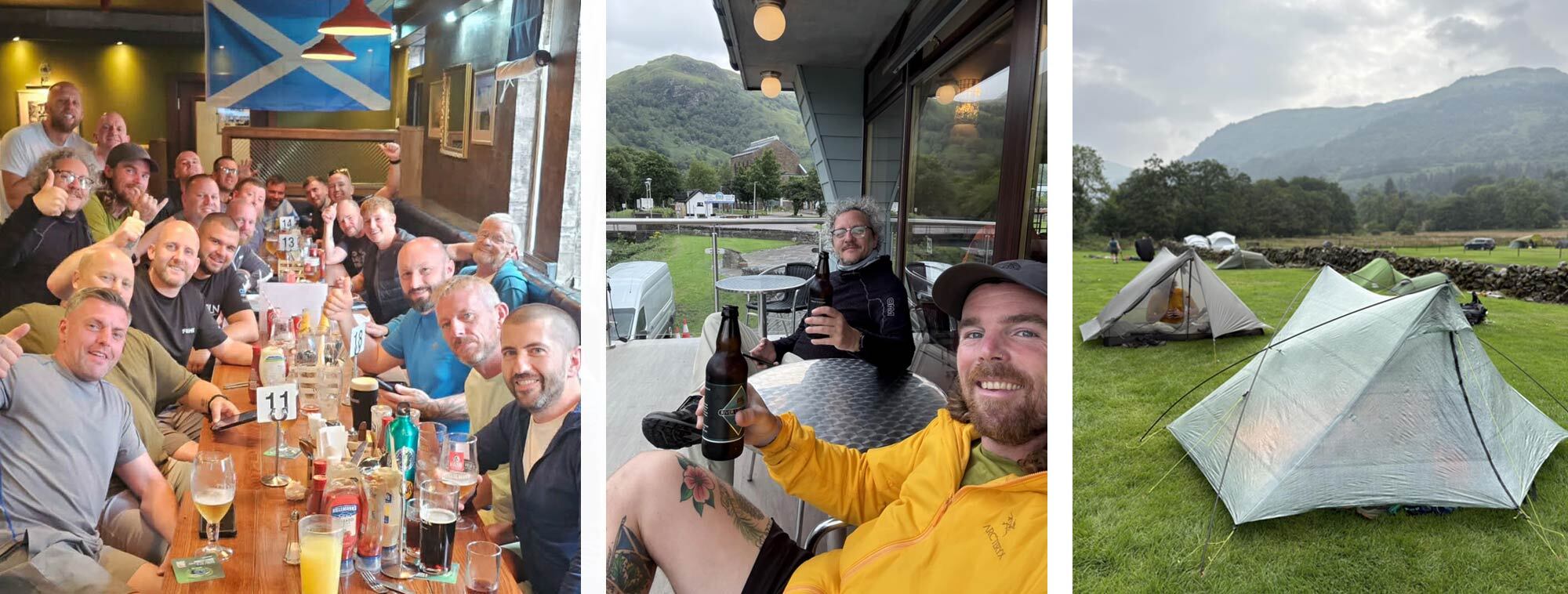

We were staying at the Beinglas campsite, a fantastic site that I will certainly stay at again. The site boasts a bar, The Stagger Inn, that serves good food, a shop where you can resupply any food or camping equipment you may be lacking, along with the usual laundry, shower facilities, and a drying room.

We didn't make it past The Stagger Inn; we met up with Mark once again, as well as our new cohort of hiking mates, Shawn and Steve. Here we ate, I went for haggis, neeps and tatties, and drank before meandering over to pitch our tents then walking the short distance to the Drovers Inn. The Drovers Inn dates back over 300 years to 1715 (which, by my calculation, makes it older than the Clachan Inn). With its stuffed animals, including a bear wearing a kilt, creaking floors, and dim candlelight, it feels more like a museum than a pub, like if Hogwarts sold beer.

Loch Lomond was now behind us, the WHW was opening the door to wilder, more scenic landscapes.

Day Four, Inverarnan to Bridge of Orchy 18.7 miles ( 30.1km)

We were up and off early, despite having tried our best to drink Hogwarts dry the night before. Whether it was the lingering effect of some potent potion or simply the fact that our trail legs had finally kicked in, we found ourselves making surprisingly good time.

The WHW, in stark contrast to yesterday’s undulating single-file scramble, now followed a network of 18th-century military roads built to help English troops, and in this case an English hiker, move quickly through the Highlands. The miles flew by as we passed the signposts for Crianlarich, just half a mile off the trail. I remembered this section vividly from eight years ago, but what had once been peaceful conifer woodland was now an open expanse, the trees felled for timber. Soon the path descended steadily back into the shade of dwindling forest before ducking under the railway and the A82.

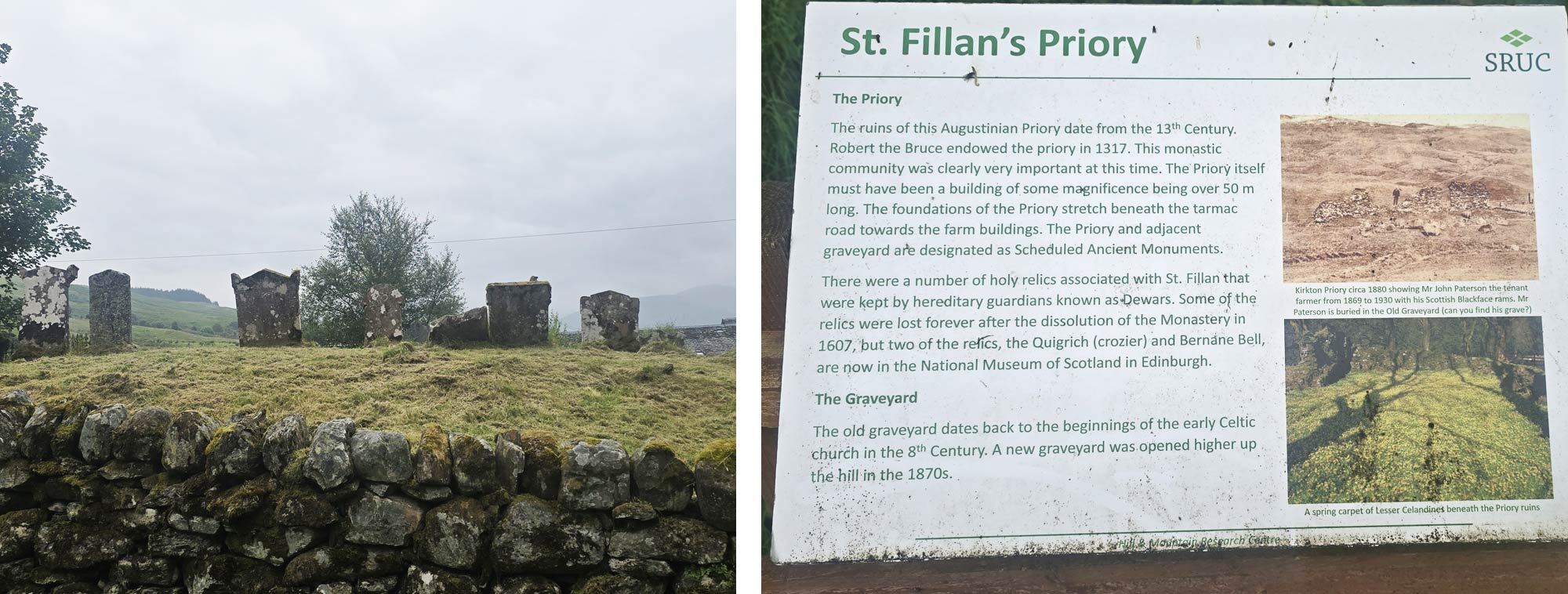

We passed the ruins of St. Fillan’s church near Kirkton Farm, the remains of a 13th-century priory established by Robert the Bruce in honour of St. Fillan, an 8th-century Irish monk whose relics Bruce is said to have carried into battle at Bannockburn. Now there is just a small cemetery and an information plaque to mark the spot. Here we lingered for a moment among the tumbled walls and graves, letting the weight of centuries settle in, before moving on.

The glen widened out, and soon the rooftops of Tyndrum came into view. Many of our fellow walkers had planned to stop at Tyndrum, which was my end point for the day 8 years ago, but it wasn't even midday when we arrived. We grabbed a bite to eat at a spot conveniently halfway through our day (are you starting to see a pattern?). We took the opportunity to visit the famous Green Welly Stop, part café, part outdoor shop, and part Scottish institution, the kind of place where you can fuel up and stock up. It was so busy it felt almost jarring after the solitude of the trail. We quickly headed out of town and joined The Way once again.

Under the watchful gaze of Beinn Odhar and the foreboding shadow of Beinn Dorain, the path hugs the flanks of these great mountains as it winds north toward the Bridge of Orchy. Beinn Odhar rises to 901 metres and though technically just shy of Munro status, dominates the glen with its steep, conical slopes. Beinn Dorain, at 1,076 metres, is one of Scotland’s best-loved Munros, and as we paused beneath it, we were transfixed by paragliders soaring overhead.

We were staying at the Bridge of Orchy railway station, the old waiting rooms have been converted into a small, cosy hostel with five sets of bunk beds. There is also a small honesty shop, which had an impressive amount of supplies of which we took advantage, getting breakfast and some snacks for the next day. We claimed our beds, stashed our packs, and headed to the Bridge of Orchy hotel for a bite to eat.

After nearly 19 miles it was a relief to sit with a hot meal knowing we had crossed into the very heart of the Highlands.

Day Five, Bridge of Orchy to Kinlochleven 18.8 miles (30.33km)

It felt odd to think this was our penultimate day as we packed up and set off in the drizzle. It seemed like we had only just begun, yet the end was already creeping up on us. We crossed the Bridge of Orchy, a handsome stone bridge that was built in 1751, as the path steadily climbed.

Over Màm Carraigh the trail opened to moody vistas of Loch Tulla, the mist and drizzle weaving a shifting curtain that made the loch feel ethereal, close at hand, yet half-hidden. The same ghostly haze clung to the mountain tops and spilled into the surrounding glens, softening the whole landscape. We descended to the Inveroran valley where the whitewashed Inveroran Hotel sits in splendid isolation. We quickly hurried inside, not sheltering from the weather, but from Scotland's most notorious of beasts, the midge.

So, as of yet, I haven't had to comment on these wee beasties and as we were walking The Way in June, the number one piece of advice is, well, not to. The midges at this time of year can be so abundant that they can ruin even the hardiest hiker's trip. My hiking season in the highlands is from January to May, then from September to January, so it's a testament to how much I valued Brian's friendship that I was here in the “off” season. They are that notorious. We were armed with Smidge and headnets, but still in the moist lowland, we were swarmed.

We dove into the small shop attached to the Inveroran Hotel, “Shut the bloody door!” the otherwise friendly shopkeeper bellowed, as we ordered coffee. We chatted to the shopkeeper, who informed us he had been working in or around the shop for the last 16 years. I asked him, “When do you remember the midges being at their worst?” he pondered this a second before answering “Tuesday”. More hikers came in, and more demands to shut the door were made. As we headed out of the shop, the shopkeeper was arming himself with hairspray and a lighter, so we made tracks.

Before I set off on the WHW, a hiking friend warned me that the trail was ‘a motorway’ because it’s so busy. In truth, I never felt the crowds spoiled my sense of solitude. The only times I really noticed the throng of people were in villages and towns, or at obvious gathering spots like the Beech Tree Inn (all the way back on our first day, which already felt like a lifetime ago) and the Green Welly Stop. However, now with views over the great expanse of Rannoch Moor, I saw the great swathes of people further on up the trail.

Maybe it was because these were the first truly unobstructed views of the trail on this trip, or it was simply the weekend bringing more people out. More likely, it was also due to this stretch between the Bridge of Orchy and the King's House being one of the most stunning, yet most accessible, paths in the whole of the UK. I suspect it was a little of all three. Neither the crowd nor the weather could dampen my spirits. As we followed the old military road around the flank of Meall a’ Bhuiridh, the vast expanse of Glencoe opened before us, still wrapped in the morning’s ethereal mist, the silhouette of the great Buachaille Etive Mòr, guarding the entrance to the great glen, slowly revealing itself with each step forward.

By midday, we had reached the famous Kingshouse, which has changed immeasurably since I first visited eight years ago. What was once a simple inn is now more of a complex with a hotel, bunkhouses, and camping on site. We stopped for lunch, my second venison burger of the trip, but didn’t linger long as there were still miles to cover, most notably the Devil’s Staircase.

Despite the name, which I’m sure has struck fear into the hearts of many setting off on the WHW, the climb is more manageable than it sounds. Built in the 18th century, the zigzagging path rises steadily to 548 m, the highest point on the trail. It’s a slog, yes, but pace yourself and the switchbacks do much of the work. At the top, the reward is immense: panoramic views of Glencoe spread out below, Buachaille Etive Mòr still towering above, while to the north the serrated ridges of the Mamores stretch across the horizon. And far beyond, the end is literally in sight, the summit of Ben Nevis.

The descent to Kinlochleven is long and at times punishing, dropping almost 1,800 ft to sea level. Eventually, the trail becomes a winding vehicle track, running alongside enormous pipes that plunge straight down the hillside from Blackwater Reservoir to the hydroelectric station. This engineering feat made Kinlochleven the first place in the world where every house was connected to electricity, a notable achievement for a remote Highland village.

By the time we reached the Blackwater Hostel, where we were camping, we were ready for a rest. A quick trip out for food somehow landed us in the middle of a stag do, all of them, unbelievably, also walking the WHW. We ducked out before things got too messy and slipped back to our tents for the night.

As I crawled into my tent that night, it was hard to believe tomorrow would be our final day on the trail, one last climb, one last descent, and the WHW would be over.

Day Six, Kinlochleven to Fort William 15.5 miles (25 km)

The last day started slowly, but with only 15 miles to cover, and all day to do them, we started late. We left Kinlochleven in good weather, though the climb out of town was as brutal as I remembered. If the Devil’s Staircase truly deserves its name, then I dub this ascent the “Midge’s Ladder” (and fully expect it to appear on the next printing of the OS maps), which, if you can’t tell, is much worse. On my previous crossing, I remembered it with unreserved trauma, and this time was no different. Huffing, panting, swearing, and sweating, I hauled myself up the last real climb of the WHW, onto the Lairig Mòr, the “Great Pass,” a name that feels subtly fitting.

We emerged into a wide U-shaped valley that was once a main route into the Highlands; now it is a beautiful, empty glen with endless sky views. The trail through Lairig Mòr is relatively flat and easy underfoot, and the miles slipped by. We stopped for a bite to eat, our first (and only) dehydrated meal of the trip, a Real Turmat Taco Bowl (10/10).

From there, The Way curves around the flank of Mullach nan Coirean before descending into Glen Nevis, where the vast bulk of Ben Nevis, wrapped in cloud, dominated the horizon. The Way then becomes a forest track, then a minor road, then a main road, until suddenly you are in the centre of Fort William, passing gift shops, outdoor stores, pubs, and cafés. And then, without much ceremony, you arrive at the bronze statue, “The Man with Sore Feet,” sitting, eternally waiting. We joined him on the bench, sat back, and quietly contemplated the fact that we had completed the West Highland Way (again).

As I sat beside the bronze “Man with Sore Feet,” I couldn’t help but think back to my first time here, eight years ago, when the West Highland Way felt impossibly vast, wild, and daunting. Then it had been a rite of passage, the path that turned me into a hiker. This time, I carried fewer doubts and far better kit, but the trail still managed to surprise me, humble me, and to remind me why I keep walking. Walking it again wasn’t about proving I could; it was about rediscovering that spark of adventure with new eyes and sharing it with Brian. Journeys like this don’t end when the miles are done. They stay with you, woven into the landscapes, the laughter, the aches, and the people who walk them with you.

Read Andy's Ultralight 5.7kg Kit List for the West Highland Way

|

||

|

||

| Andy Neil |

||

|

Andy has been a keen long-distance hiker and wild camping enthusiast since he completed the Cleveland Way in 2015. Since then, he has walked thousands of trail miles all over the UK and is an active member of the Wild Camping UK community, being an admin of the largest wild camping community on Facebook. He strongly advocates for responsible wild camping and believes it is important to leave no trace when camping in the wilderness. He joined the UOG team in 2021 and works as a website developer and content creator. |

||